Apocalypse Now is a 1979 American epic war film set during the Vietnam War. The plot revolves around two US Army special operations officers, one of whom, Captain Benjamin L. Willard (Martin Sheen) of MACV-SOG, is sent into the jungle to assassinate the other, the rogue and presumably insane Special Forces Colonel Walter E. Kurtz (Marlon Brando). The film was produced and directed by Francis Ford Coppola from a script by Coppola and John Milius. The script is based on Joseph Conrad's novella Heart of Darkness, and also draws elements from Michael Herr's Dispatches, the film version of Conrad's Lord Jim (which shares the same character of Marlow with Heart of Darkness), and Werner Herzog's Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1992).[1]

The film became notorious in the entertainment press due to its lengthy and troubled production, as documented in Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse. Marlon Brando showed up to the set overweight and Martin Sheen suffered a heart attack. The production was also beset by extreme weather that destroyed several expensive sets. In addition, the release date of the film was delayed several times as Coppola struggled to come up with an ending and edit the millions of feet of footage that he had shot.

The film won the Cannes Palme d'Or and was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture and the Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama.

Coppola's interpretation of the iconic Kurtz character has been widely believed to have been modeled after Tony Poe, a highly-decorated and highly unorthodox Vietnam-era Paramilitary Officer from the CIA's Special Activities Division.[2] Poe was known to drop severed heads into enemy-controlled villages as a form of psychological warfare and to use human ears to record the number of enemies his indigenous troops had killed. He would send these ears back to his superiors as proof of his efforts deep inside Laos.[3][4] Coppola, however, denies that Poe was a primary influence and instead says the character was loosely based on Special Forces Colonel Robert Rheault, whose 1969 arrest over the murder of a suspected double agent generated substantial news coverage.[5]

Plot[]

It is 1969 and the Vietnam War is at its height. CPT Benjamin L. Willard (Martin Sheen) has returned to Saigon; a seasoned special operations veteran, he is deeply troubled and apparently no longer adjusted to civilian life and excessively drinks cognac. Two intelligence officers, LTG Corman (G. D. Spradlin) and COL Lucas (Harrison Ford), as well as a government man (Jerry Ziesmer), approach him with a special mission: journey up the fictional Nung River into the remote Cambodian jungle to find COL Walter E. Kurtz (Marlon Brando), a non compliant member of the US Army Special Forces.

They state that Kurtz, once considered a model officer and future general, has allegedly gone insane and is commanding a legion of his own Montagnard troops deep inside the forest in neutral Cambodia. Their claims are supported by very disturbing radio broadcasts and/or recordings made by Kurtz himself. Willard is ordered to undertake a mission to find Kurtz and terminate the Colonel's command "with extreme prejudice."

Willard studies the intelligence files during the boat ride to the river entrance and learns that Kurtz, isolated in his compound, has assumed the role of a warlord and is worshiped by the natives and his own loyal men. Willard learns much later that another officer, Colby (Scott Glenn), sent earlier to kill Kurtz, may have become one of his lieutenants.

Willard begins his trip up the Nung River on a PBR (Patrol Boat, Riverine), with an eclectic crew composed of the obstinate and formal QMC George Phillips (Albert Hall), the Navy PBR boat captain; GM3 Lance B. Johnson (Sam Bottoms), a tanned all-American California surfer; GM3 Tyrone Miller (Laurence Fishburne), a.k.a. "Mr. Clean", a black 17-year-old from "some South Bronx shit-hole"; and EN3 Jay "Chef" Hicks (Frederic Forrest), an aspiring sauce chef from New Orleans, whom Willard describes as "wrapped too tight for Vietnam, probably wrapped too tight for New Orleans".

The PBR arrives at a landing zone where Willard and the crew meet up with LTC Bill Kilgore (Robert Duvall), the eccentric commander of 1/9cav AirCav, following a massive and hectic mopping-up operation of a conquered enemy village. Kilgore, a keen surfer, recognizes and befriends Johnson. Later, he learns from one of his men, Mike, that the beach down the coast which marks the opening to the river is perfect for surfing, a factor which persuades him to capture it. The problem is, his troops explain, it's "Charlie's point" and heavily fortified. Dismissing this complaint with the explanation that "Charlie don't surf!," Kilgore orders his men to saddle up in the morning to capture the town and the beach. Riding high above the coast in a fleet of Hueys accompanied by OH-6As, Kilgore launches an attack on the beach. The scene, famous for its use of Richard Wagner's "Ride of the Valkyries," ends with the soldiers surfing the barely claimed beach amidst skirmishes between infantry and VC. After helicopters swoop over the village and demolish all visible signs of resistance, a giant napalm strike in the nearby jungle dramatically marks the climax of the battle. Kilgore exults to Willard, "I love the smell of napalm in the morning," which he says smells "like... victory" as he recalls a battle in which a hill was bombarded with napalm for over twelve hours.

The lighting and mood darken as the boat navigates upstream and Willard's silent obsession with Kurtz deepens. Incidents on the journey include a run-in with a tiger while Willard and Chef search for mangoes. The boat then moves up river and watches a USO show featuring Playboy Bunnies and a centerfold that degenerates into chaos.

Moving up the river, Phillips spots a sampan and against Willard's advice they make the boat stop and inspect it. As Chef hostilely searches the sampan, one of the civilians makes a sudden movement towards a barrel, causing Clean to open fire on the wooden boat, killing all the civilians save for one badly wounded survivor. Chef discovers that the barrel contained the pet puppy of one of the sampan's crew. An argument breaks out between Willard and Phillips over whether to take the survivor to receive medical attention. Willard ends the argument by shooting the survivor, calmly stating "I told you not to stop."

The boat moves up river to a surreal stop at the American outpost at the Do Long bridge, the last U.S. Army outpost on the river. The boat arrives during a North Vietnamese attack on the bridge, which is under constant construction. Upon arrival, Willard receives the last piece of the dossier from a lieutenant named Carlson, along with mail for the boat crewmen. Willard and Lance, who has taken LSD, go ashore and they make their way through t

he trenches where they encounter many panicked, leaderless soldiers. Realizing the situation has devolved into chaos, Willard and Lance return to the boat. The chief tries to convince Willard not to continue on with his mission, of which he does not truly know the details. He compares the mission to the Do Long bridge, which is destroyed every night but rebuilt so that it can be said the road is open, and that the mission is insignificant. In response, Willard snaps at Phillips to get him upriver. As the boat departs, the NVA launch an artillery strike on the bridge, destroying it.

The next day, the PBR, while its crew is busy reading mail, is ambushed by Viet Cong hiding in the trees by the river which results in Clean's death as he listens to a tape from his mother. The chief, who had a father-son relationship with Clean, becomes openly hostile to Willard. As they approach the outskirts of Kurtz' camp, Montagnard villagers begin firing toy arrows at them. The crew opens fire until the chief is hit by a real spear. As Willard hovers over the mortally wounded Chief Phillips, he attempts to kill Willard by pulling him onto the spearpoint protruding from his chest. Willard subsequently smothers the chief with his bare hands.

After arriving at Kurtz' outpost, Willard leaves Chef behind with orders to call in an airstrike on the village if he does not return. They are met by a seemingly crazed freelance photographer (Dennis Hopper), who explains Kurtz's greatness and philosophical skills to provoke his people into following him. Willard also encounters Colby, in an apparently shell-shocked state. Brought before Kurtz and held in captivity in a darkened temple, Willard’s constitution appears to weaken as Kurtz lectures him on his theories of war, humanity, and civilization. Kurtz explains his motives and philosophy in a famous and haunting monologue in which he praises the ruthlessness of the Viet Cong he witnessed following one of his own humanitarian missions.

While bound outside in the pouring rain, Willard is approached by Kurtz, who places the severed head of Chef in his lap, after Chef had been caught trying to call in the airstrike. Coppola makes little explicit, but we come to believe that Willard and Kurtz develop an understanding nonetheless; Kurtz wishes to die at Willard's hands, and Willard, having subsequently granted Kurtz his wish, is offered the chance to succeed him in his warlord-demigod role. Juxtaposed with a ceremonial slaughtering of a Water Buffalo, Willard enters Kurtz's chamber during one of his message recordings, and kills him with a machete. This entire sequence is set to "The End" by The Doors, as is the sequence at the very beginning of the film. Lying bloody and dying on the ground, Kurtz whispers "The horror... the horror," a line taken directly from Conrad's novella. Willard drops his weapon as in turn the natives do in a symbolic act of laying down of arms,he walks through the now-silent crowd of natives and takes Johnson (who is now fully integrated into the native society) by the hand. He leads Johnson to the PBR, and floats away as Kurtz's final words echo in the wind as the screen fades to black.

Cast[]

- Martin Sheen as Captain Benjamin L. Willard. Willard is a veteran officer who has been serving in Vietnam for three years. He wears the insignia of the elite US Army Rangers, and it is implied Willard had done missions for MACV-SOG and the CIA. An attempt to re-integrate into home-front society had apparently failed prior to the time at which the movie is set, and so he returned to the war-torn jungles of Vietnam, where he seemed to feel more at home.

- Marlon Brando as Colonel Walter E. Kurtz, a highly decorated American Army Special Forces officer who goes renegade. He runs his own operations out of Cambodia and is feared by the US military as much as the Vietnamese.

- Robert Duvall as Lieutenant Colonel William "Bill" Kilgore, cavalry battalion commander and surfing fanatic. Kilgore is a strong leader who loves his men dearly but has methods that appear out-of-tune with the setting of the war.

- Frederic Forrest as Engineman 3rd Class Jay "Chef" Hicks, a tightly-wound former chef from New Orleans who is horrified by his surroundings.

- Sam Bottoms as Gunner's Mate 3rd Class Lance B. Johnson, a former professional surfer from California who spends the majority of the journey on a drug binge.

- Laurence Fishburne as Gunner's Mate 3rd Class Tyrone "Mr. Clean" Miller, the 17 year-old cocky South Bronx-born crewmember. He resents the inward nature of Willard.

- Albert Hall as Chief Quartermaster George Phillips. The chief runs a tight ship and frequently clashes with Willard over authority. Has a father-son relationship with Clean.

- G.D. Spradlin as Lieutenant General Corman, military intelligence (G-2) an authoritarian officer who fears Kurtz and wants him removed.

- Jerry Ziesmer as a mysterious man in civilian attire who sits in on Willard's initial briefing, is the only one calm enough to eat during the briefing, and whose only line in the movie is the famous "Terminate with extreme prejudice".

- Dennis Hopper as an American Photojournalist, a crazed photographer who intercuts poetry with obscene cynicism. Stranded in Kurtz's camp. Takes pictures from a camera that may or may not contain film. According to the DVD commentary of Redux, the journalist is a supposed to be a real life photographer who went missing in Vietnam in 1966. Coppola stated that Hopper's character is supposed to be the real life journalist Sean Flynn years later.

- Harrison Ford as Colonel Lucas, aide to Corman and general information specialist. Despite his rank, he often appears nervous and jittery regarding Kurtz and the mission.

- Scott Glenn as Captain Richard M. Colby, previously assigned Willard's current mission before he defected to Kurtz's private army and sent a message to his wife telling her to sell everything they owned (but he goes on to tell her to sell their children, as well).

- Bill Graham as Agent (announcer and in charge of Playmate's show)

- Cynthia Wood as Playmate of the Year

- Colleen Camp as Playmate, "Miss May"

- Linda Carpenter as Playmate, "Miss August"

- Christian Marquand as Hubert de Marais (redux version)

- Aurore Clément as Roxanne Sarraut-de Marais (redux version), a widow and influential figure at the plantation.

- Roman Coppola as Francis de Marais (redux version), the surrogate leader of the French residents and strong vocal opponent of American action.

- Francis Coppola himself has a cameo as a director filming beach combat. He shouts "Don't look at the camera, keep on fighting!" DP Vittorio Storaro plays the cameraman by Coppola's side.

Several actors who were, or later became, prominent stars have minor roles in the movie including Harrison Ford, G. D. Spradlin, Scott Glenn, and R. Lee Ermey. Fishburne was only fourteen years old when shooting began in March 1976, and he lied about his age in order to get cast in his role.[6] Apocalypse Now took so long to finish that Fishburne was seventeen (the same age as his character) by the time of its release.

Adaptation[]

Although inspired by Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness, the film deviates extensively from its source material. The novella, based on Conrad's real experiences as a steam paddleboat captain in Africa, is set in the Congo Free State during the 19th century. Kurtz and Marlow (who is named Willard in the movie) both work for a Belgian trading company that brutally exploits its native African workers.

When Marlow arrives at Kurtz's outpost, he discovers that Kurtz has gone insane and is lording over a small tribe as a god. The novella ends with Kurtz dying on the trip back and the narrator musing about darkness of the human psyche: "the heart of an immense darkness."

In the novella, Marlow is the pilot of a river boat sent to collect ivory from Kurtz's outpost, only gradually becoming infatuated with Kurtz. In fact, when he discovers Kurtz in terrible health, Marlow makes a concerted effort to bring him home safely. In the movie, Willard is an assassin dispatched to kill Kurtz. Nevertheless, the depiction of Kurtz as a god-like leader of a tribe of natives and his malarial fever, Kurtz's written exclamation "Exterminate the brutes!" (which appears in the film as "Drop the bomb. Exterminate them All!") and his final lines "The horror! The horror!" are taken from Conrad's novella.

Coppola argues that many episodes in the film—the spear and arrow attack on the boat, for example—respect the spirit of the novella and in particular its critique of the concepts of civilization and progress. Other episodes adapted by Coppola, the Playboy bunnies (Sirens) exit, the lost souls, "taking me home" attempting to reach the boat and Kurtz' tribe of (white-faced) natives parting the canoes (gates of Hell) for Willard, (with Chef and Lance) to enter the camp are likened to Virgil and "The Inferno" (Divine Comedy) by Dante. While Coppola replaced European colonialism with American interventionism, the message of Conrad's book is still clear.[7]

Development[]

While working as an assistant for Francis Ford Coppola on The Rain People, George Lucas encouraged his friend and filmmaker John Milius to write a Vietnam War film.[8] Milius came up with the idea for adapting the plot of Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness to the Vietnam War setting.[9] He had no desire to direct the film and felt that George Lucas was the right person for the job. However, filmmaker Carroll Ballard claims that Apocalypse Now was his idea in 1967 before Milius had written his screenplay. Ballard had a deal with producer Joel Landon and they tried to get the rights to Conrad's book but were unsuccessful. Lucas acquired the rights but failed to tell Ballard and Landon.[9]

Screenplay[]

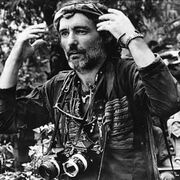

John Milius

Coppola gave Milius $15,000 to write the screenplay with the promise of an additional $10,000 if it got made.[10] Milius claims that he wrote the screenplay in 1969[9] and it was originally called The Psychedelic Soldier.[11] He wanted to use Conrad's novel as "a sort of allegory. It would have been too simple to have followed the book completely".[10] He based the character of Willard and some of Kurtz on a friend of his, Fred Rexer, who had experienced, first-hand, the scene related by Marlon Brando's character where the arms of villagers are hacked off by the Viet Cong. At one point, Coppola told Milius, "write every scene you ever wanted to go into that movie",[9] and he wrote ten drafts — over a thousand pages.[12] Milius changed the film's title to Apocalypse Now after being inspired by a button badge popular with hippies during the '60s that said, "Nirvana Now". He was also influenced by an article written by Michael Herr entitled, "The Battle for Khe San", which referred to drugs, rock 'n' roll, and people calling airstrikes down on themselves.[9]

Pre-production[]

Coppola was drawn to Milius' script, which he described as "a comedy and a terrifying psychological horror story".[13] George Lucas was originally interested in directing and planned to shoot it after making THX 1138 with principal photography to start in 1971. He planned to shoot the film in the rice fields between Stockton and Sacramento, California.[10] His friend and producer Gary Kurtz traveled to the Philippines, scouting suitable locations. They intended to shoot the film on a $2 million budget, documentary style, using 16 mm cameras, and real soldiers.[9] However, Lucas became involved with American Graffiti and this delayed the production of Apocalypse Now.[10] In the spring of 1974, Coppola discussed with friends and co-producers Fred Roos and Gary Frederickson the idea of producing the film.[14]

While making The Godfather Part II, Coppola asked Lucas and then Milius to direct Apocalypse Now, but both men were involved with other projects,[14] in Lucas' case, he got the go-ahead to make his pet project, Star Wars, and declined the offer to direct Apocalypse Now.[9] Coppola was determined to make the film and pressed ahead himself. He envisioned the film as a definitive statement on the nature of modern war, the difference between good and evil, and the impact of American society on the rest of the world. The director said that he wanted to take the audience "through an unprecedented experience of war and have them react as much as those who had gone through the war".[13]

In 1975, while promoting The Godfather Part II in Australia, Coppola and his producers scouted possible locations for Apocalypse Now in Cairns in northern Queensland that had jungle resembling Vietnam.[15] He decided to make his film in the Philippines for its access to American equipment and cheap labor. Production coordinator Fred Roos had already made two low-budget films there for Monte Hellman and had friends and contacts in the country.[13] Coppola spent the last few months of 1975 revising Milius' script and negotiating with United Artists to secure financing for the production. According to Frederickson, the budget was estimated between $12–14 million.[16] Coppola's American Zoetrope assembled $8 million from distributors outside the United States and $7.5 million from United Artists who assumed that the film would star Marlon Brando, Steve McQueen, and Gene Hackman.[13] Frederickson went to the Philippines and had dinner with President Ferdinand Marcos to formalize support for the production and to allow them to use some of the country's military equipment.[17]

Casting[]

Steve McQueen was Coppola's first choice to play Willard but the actor did not accept because he did not want to leave America for 17 weeks.[13] Al Pacino was also offered the role but he too did not want to be away for that long period of time and was afraid of falling ill in the jungle as he had done in the Dominican Republic during the shooting of The Godfather Part II.[13] Jack Nicholson, Robert Redford, and James Caan were approached to play either Kurtz or Willard.[18] Coppola and Roos had been impressed by Martin Sheen's screen test for Michael in The Godfather and he became their top choice to play Willard but the actor had already accepted another project and Harvey Keitel was cast in the role based on his work in Martin Scorsese's Mean Streets.[19] By early 1976, Coppola had persuaded Marlon Brando to play Kurtz for a then-unheard of fee - $3.5 million for a month's work on location in September 1976. Dennis Hopper was cast as a kind of Green Beret sidekick for Kurtz and when Coppola heard him talking nonstop on location, he remembered putting "the cameras and the Montagnard shirt on him, and we shot the scene where he greets them on the boat".[18]

Principal photography[]

On March 1, 1976, Coppola and his family flew to Manila and rented a large house there for the five-month shoot.[18] Sound and photographic equipment had been coming in from California on a regular basis since late 1975. Principal photography began three weeks later. Within a few days, Coppola was not happy with Harvey Keitel's take on Willard, saying that the actor "found it difficult to play him a passive onlooker".[18] After viewing early footage, the director took a plane back to Los Angeles and replaced Keitel with Martin Sheen.

Tropical rains wrecked the sets at Iba and on May 26, 1976, production was closed down.[20] Dean Tavoularis remembers that it "started raining harder and harder until finally it was literally white outside, and all the trees were bent at forty-five degrees".[20] One part of the crew was stranded in a hotel and the others were in small houses that were immobilized by the storm. The Playboy Playmate set had been destroyed, ruining a month's shooting that had been scheduled. Most of the cast and crew went back to the United States for six to eight weeks. Tavoularis and his team stayed on to scout new locations and rebuild the Playmate set in a different place. Also, the production had bodyguards watching constantly at night and one day the entire payroll was stolen. According to Coppola's wife, Eleanor, the film was six weeks behind schedule and $2 million over budget.[20]

Coppola flew back to the U.S. in June 1976. He read a book about Genghis Khan to get a better handle on the character of Kurtz.[20] After filming commenced, Marlon Brando arrived in Manila very overweight and began working with Coppola to rewrite the ending.[21] The director downplayed Brando's weight by dressing him in black, photographing only his face, and having another, taller actor double for him in an attempt to portray Kurtz as an almost mythical character.[21]

In the days after Christmas 1976, Coppola viewed a rough assembly of the footage he had to date but still needed to improvise an ending. He returned to the Philippines in early 1977 and resumed filming.[21] On March 5, 1977, Sheen had a heart attack and struggled for a quarter of a mile to reach help.[22] He was back on the set on April 19. A major sequence in a French plantation cost hundreds of thousands of dollars but was cut from the final film. Rumors began to circulate that Apocalypse Now had several endings but Richard Beggs, who worked on the sound elements, said, "There were never five endings, but just the one, even if there were differently edited versions".[22] These rumors came from Coppola departing frequently from the original screenplay. Coppola admitted that he had no ending because Brando was too fat to play the scenes as written in the original script. With the help of Dennis Jakob, Coppola decided that the ending could be "the classic myth of the murderer who gets up the river, kills the king, and then himself becomes the king — it's the Fisher King, from The Golden Bough".[22]

A water buffalo was slaughtered with a machete for the climactic scene. The scene was inspired by a ritual performed by a local Ifugao tribe which Coppola had witnessed along with his wife (who filmed the ritual later shown in the documentary Hearts of Darkness) and film crew. Although this was an American production subject to American animal cruelty laws, scenes like this filmed in the Philippines were not policed or monitored, and the American Humane Association gave the film an "unacceptable" rating.[23] Principal photography ended on May 21, 1977 and everyone headed home.[24]

Post-production[]

In the summer of 1977, Coppola told Walter Murch that he had four months to assemble the sound. Murch realized that the script had been narrated but Coppola abandoned the idea during filming.[24] Murch thought that there was a way to assemble the film without narration but it would take ten months and decided to give it another try.[25] He put it back in, recording it all himself. By September, Coppola told his wife that he felt "there is only about a 20% chance [I] can pull the film off".[26] He convinced United Artists executives to delay the premiere from May to October 1978. Sneak preview audiences remained puzzled by the logic and significance of several of the film’s key scenes, most troublingly, the film’s conclusion. Author Michael Herr received a call from Zoetrope in January 1978 and was asked to work on the film's narration based on his well-received journal about Vietnam, Dispatches.[26] Herr said that the narration already written was "totally useless" and spent a year writing various narrations with Coppola giving him very definite guidelines.[26] He then created a voice-over interior monologue for Willard that spanned virtually the entire film so that audiences immediately understood the film’s events.[26]

Murch had problems trying to make a quadraphonic soundtrack for Apocalypse Now because sound libraries were devoid of any stereo recordings of any weapons and, specifically, weapons used in Vietnam.[26] In addition, the sound material brought back from the Philippines was inadequate because the small location crew lacked time and resources sufficient to record jungle sounds and ambient noises. Murch and his crew had to fabricate the mood of the jungle on the soundtrack. Apocalypse Now would feature innovative sound technique for movies as Murch insisted on recording the most up-to-date gunfire and employed a quintuphonic soundtrack with three channels of sound behind the movie screen and two channels of sound from behind the audience.[26]

On May 1978, Coppola decided that it would not be possible to finish the film for a December release and postponed the opening until spring of 1979. He screened a "work in progress" for 900 people in April 1979 that was not well received.[27] That same year, he was invited to screen Apocalypse Now at the Cannes Film Festival.[28] United Artists were not keen on showing an unfinished version in front of so many members of the press but Coppola remembered that The Conversation won the Palme d'Or and agreed to show Apocalypse Now at the festival less than a month before it began. The week prior to Cannes, Coppola arranged three sneak previews that each featured their own slightly different versions. He allowed critics to attend the screenings and believed that they would honor the embargo placed on reviews. On May 14, Rona Barrett reviewed the film on television and called it "a disappointing failure".[28] At Cannes, Zoetrope technicians worked during the night before the screening to install additional speakers on the theater walls in order to achieve Murch's quadraphonic soundtrack.[28]

Alternate versions[]

Endings[]

At the time of its release, many rumors surrounded the ending of Apocalypse Now. Coppola stated an ending was written in haste in which Willard and Kurtz joined forces and repelled the air strike on the compound; however, Coppola never fully agreed with the two going out in apocalyptic intensity, preferring to end the film in a more encouraging manner.[citation needed]

When Coppola originally organized the ending of the movie, he had two choices. One involved Willard leading Lance by the hand as everyone in Kurtz's base throws down their weapons, and ends with images of Willard's boat pulling away from Kurtz's compound superimposed over the face of a stone idol which then fades into black. Another option showed an air strike being called and the base being blown to bits in a spectacular display, consequently killing everyone left at the base.

The original 1979 70 mm exclusive theatrical release ended with Willard's boat, the stone statue, then fade to black with no credits, save for '"Copyright 1979 Omni Zoetrope"' right after the film ends. This mirrors the lack of any opening titles and supposedly stems from Coppola's original intention to "tour" the film as one would a play: the credits would have appeared on printed programs provided before the screening began.[29] For general release in 35mm, Coppola elected to show the credits superimposed over shots of Kurtz's base exploding.[29] Rental prints circulated with this ending, and can be found in the hands of a few collectors. However, when Coppola heard that audiences interpreted this as an air strike called by Willard, Coppola pulled the film from its 35 mm run, and put credits on a black screen. In the DVD commentary, Coppola explains that the images of explosions had not been intended to be part of the story; they were intended to be seen as completely separate from the film. He had added them to the credits because he had captured the footage during the demolition of the set in the Philippines, which was filmed with multiple cameras fitted with different film stocks and lenses to capture the explosions at different speeds.

Because of the confusion over the misinterpreted ending, there are multiple slightly varying versions of the ending credits. Some TV screenings maintain the explosion footage at the end, others do not, and there are several other versions.

The first DVD of the theatrical version plays like the 70 mm version, without beginning or ending credits, but has them on a separate part of the DVD. The credits to Apocalypse Now Redux are different again: the credits play over a black background, but with ambient music by the Rhythm Devils.

Extended bootleg version[]

There is also a longer 289 minute version which circulates unofficially. It has never been officially released but circulates as a video bootleg, containing extra material not included in either the original theatrical release or the "redux" version.[30] A low-quality video transfer of a rough workprint, with a 330 minute running time, is also available unofficially.[31]

Apocalypse Now Redux[]

In 2001, Coppola released Apocalypse Now Redux in cinemas and subsequently on DVD. This is an extended version that restores 49 minutes of scenes cut from the original film. Coppola has continued to circulate the original version as well: the two versions are packaged together in the Complete Dossier DVD, released on August 15, 2006.

The longest section of added footage in the Redux version is an anticolonialism chapter involving the de Marais family's rubber plantation, a holdover from the colonization of French Indochina, featuring Coppola's two sons Giancarlo and Roman as children of the family. These scenes were removed from the 1979 cut, which premiered at Cannes. In behind-the-scenes footage in Hearts of Darkness, Coppola expresses his anger, on the set, at the technical aspects of the shot scenes, the result of tight allocation of resources. At the time of the Redux version, it was possible to digitally-enhance the footage to accomplish Coppola's vision. In the scenes, the French family patriarchs argue about the positive side of colonialism in Indochina and denounce the betrayal of the military men in the First Indochina War. Hubert de Marais argues that French politicians sacrificed entire battalions at Điện Biên Phủ, and tells Willard that the US created the Viet Cong (as the Viet Minh), to fend off Japanese invaders.

Other added material includes extra combat footage before Willard meets Kilgore, a humorous scene in which Willard's team steals Kilgore's surfboard (which sheds some light on the hunt for the mangoes), a follow-up scene to the dance of the Playboy playmates, in which Willard's team finds the playmates awaiting evacuation after their helicopter has run out of fuel, and a scene of Kurtz reading from a Time magazine article about the war, surrounded by Cambodian children.

There is a deleted scene entitled "Monkey Sampan" which was used as a way to represent the whole movie in a three minute scene. The scene shows Willard and the PBR crew suspiciously eyeing an approaching Sampan juxtaposed to Montagnard villagers joyfully singing "Light My Fire" by The Doors. As the Sampan gets closer Willard realizes there are Monkeys on it and no driver. Finally just as the two boats pass, the wind turns the sail and exposes a naked dead civilian tied to the sail boom. His body is mutilated and looks as though the man was whipped. The singing stops. It is assumed the man was tortured by the Viet Cong. As they pass on by, Chief notes out loud "That's comin' from where we're going, Captain." The boat then slowly passes the giant tail of a shot down B-52 bomber. The scene is ominous and the noise of engines way up in the sky is heard. Coppola said that he made up for cutting this scene by having the PBR pass under an airplane tail in the final cut.

Reaction[]

Cannes screening[]

A three-hour version of Apocalypse Now was screened as a "work in progress" at the 1979 Cannes Film Festival and met with prolonged applause.[32] At the subsequent press conference, Coppola criticized the media for attacking him and the production during their problems filming in the Philippines and uttered the famous quotes, "We had access to too much money, too much equipment, and little by little we went insane", and "My film is not about Vietnam, it is Vietnam".[32] The filmmaker upset newspaper critic Rex Reed who reportedly stormed out of the conference. Apocalypse Now won the Palme d'Or for best film along with Volker Schlondorff's The Tin Drum - a decision that was reportedly greeted with "some boos and jeers from the audience".[33]

Box office[]

Apocalypse Now performed well at the box office when it opened in August 1979.[32] The film initially opened in one theater in New York City, Toronto, and Hollywood, grossing USD $322,489 in the first five days. It ran exclusively in these three locations for four weeks before opening in an additional 12 theaters on October 3, 1979 and then several hundred the following week.[34] The film grossed over $78 million domestically with a worldwide total of approximately $150 million.[29]

The film was re-released on August 28, 1987 in six cities to capitalize on the success of Platoon, Full Metal Jacket and other Vietnam War movies.[35] New 70mm prints were shown Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Jose, Seattle, St. Louis, and Cincinnati — cities where the film did financially well in 1979. The film was given the same kind of release as the exclusive engagement in 1979 with no logo or credits and audiences were given a printed program.[35]

Critical response[]

In his original review, Roger Ebert wrote, "Apocalypse Now achieves greatness not by analyzing our 'experience in Vietnam', but by re-creating, in characters and images, something of that experience".[36] In his review for the Los Angeles Times, Charles Champlin wrote, "as a noble use of the medium and as a tireless expression of national anguish, it towers over everything that has been attempted by an American filmmaker in a very long time".[34]

Ebert added Coppola's film to his list of Great Movies, stated: "Apocalypse Now is the best Vietnam film, one of the greatest of all films, because it pushes beyond the others, into the dark places of the soul. It is not about war so much as about how war reveals truths we would be happy never to discover".[37]

Legacy[]

Today, the film is widely regarded as a masterpiece of the New Hollywood era. It is on the AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies list at number 28. Kilgore's quote "I love the smell of napalm in the morning" was number 12 on the AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movie Quotes list. In 2002, Sight and Sound magazine polled several critics to name the best film of the last 25 years and Apocalypse Now was named number one. It was also listed as the second best war film by viewers on Channel 4's 100 Greatest War Films, and ranked number 1 on Channel 4's 50 Films To See Before You Die. In a 2004 poll of UK film fans, Blockbuster listed Kilgore's eulogy to napalm as the best movie speech.[38] The helicopter attack to the song of Ride of the Valkyries was chosen as the most memorable film scene ever by the Empire magazine.

Awards and honors[]

Wins

- Academy Award for Best Cinematography (Vittorio Storaro)

- Academy Award for Best Sound (Walter Murch, Mark Berger, Richard Beggs, Nathan Boxer)

- Cannes Film Festival: Palme d'Or[39]

- Golden Globe Award for Best Director (Francis Ford Coppola)

- Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actor (Robert Duvall)

- Golden Globe Award for Best Original Score (Carmine Coppola & Francis Ford Coppola)

In 2000, Apocalypse Now was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Nominations

- Academy Award for Best Picture

- Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama

- Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor — (Robert Duvall)

- Academy Award for Best Art Direction — Set Decoration (Angelo P. Graham, George R. Nelson and Dean Tavoularis)

- Academy Award for Directing (Francis Ford Coppola)

- Academy Award for Film Editing (Lisa Fruchtman, Gerald B. Greenberg, Richard Marks and Walter Murch)

- Best Writing, Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium (Francis Ford Coppola & John Milius)

- WGA Award for Best Drama Written Directly for the Screen (John Milius & Francis Ford Coppola)

- Grammy Award for Best Original Score Written for a Motion Picture (Carmine Coppola & Francis Ford Coppola)

American Film Institute recognition

- 1998 AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies #28

- 2005 AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movie Quotes:

- "I love the smell of napalm in the morning," #12

- 2007 AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) #30

Home video release aspect ratio issues[]

The first home video releases of Apocalypse Now were pan-and-scan versions of the original 35 mm Technovision anamorphic 2.35:1 print, and the closing credits, white on black background, were presented in compressed 1.33:1 full-frame format to allow all credit information to be seen on standard televisions. The first letterboxed appearance (on laserdisc on 12-29-1991) cropped the film to a 2:1 aspect ratio (conforming to the Univisium spec created by cinematographer Vittorio Storaro), featuring a small degree of pan-and-scan processing — notably in the opening shots in Willard's hotel room, featuring a composite montage — at the insistence of Coppola and Storaro. The end credits, from a videotape source rather than a film print, were still crushed for 1.33:1 and zoomed to fit the anamorphic video frame. All DVD releases have maintained this aspect ratio in anamorphic widescreen, but present the film without the end credits, which were treated as a separate feature. As a DVD extra, the footage of the explosion of the Kurtz compound was featured without text credits but included a commentary by director Coppola explaining the various endings based on how the film was screened. On the cover of the Redux DVD, Willard is erroneously listed as "Lieutenant Willard".

References[]

Notes[]

- ↑ Peary, Gerald. Francis Ford Coppola, Interview with Gerald Peary. GeraldPeary.com. Retrieved on 2007-03-14.

- ↑ Leary, William L. "Death of a Legend". Air America Archive. Retrieved on 2007-06-10.

- ↑ Warner, Roger. Shooting at the Moon.

- ↑ Ehrlich, Richard S. (2003-07-08). "CIA operative stood out in 'secret war' in Laos". Bangkok Post. http://www.geocities.com/asia_correspondent/laos0307ciaposhepnybp.html. Retrieved on 10 June 2007.

- ↑ Isaacs, Matt. "Agent Provocative", SF Weekly, 1999-11-17. Retrieved on 2009-05-02.

- ↑ Cowie 2001, p. 19.

- ↑ Heart of Darkness & Apocalypse Now: A comparative analysis of novella and film

- ↑ Cowie 2001, p. 2.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 Cowie 1990, p. 120.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Cowie 2001, p. 5.

- ↑ Cowie 2001, p. 3.

- ↑ Cowie 2001, p. 7.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 Cowie 1990, p. 121.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Cowie 2001, p. 6.

- ↑ Cowie 2001, p. 12.

- ↑ Cowie 2001, p. 13.

- ↑ Cowie 2001, p. 16.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Cowie 1990, p. 122.

- ↑ Cowie 2001, p. 18.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Cowie 1990, p. 123.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Cowie 1990, p. 124.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Cowie 1990, p. 125.

- ↑ Template:Cite url

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Cowie 1990, p. 126.

- ↑ Cowie 1990, pp. 126-127.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 26.5 Cowie 1990, p. 127.

- ↑ Cowie 1990, p. 128.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Cowie 1990, p. 129.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Cowie 1990, p. 132.

- ↑ Coates, Gordon. "Coppola's slow boat on the Nung", The Guardian, October 17, 2008. Retrieved on 2008-10-17.

- ↑ Sleeper, Light. "The Labour of Coppola's Twice-Born Film: The "Apocalypse Now Workprint"". Retrieved on 2009-04-03.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Cowie 1990, p. 130.

- ↑ "Sweeping Cannes", Time, June 4, 1979. Retrieved on 2008-11-22.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Cowie 1990, p. 131.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Harmetz, Aljean. "Apocalypse Now to Be Re-released", New York Times, August 20, 1987. Retrieved on 2008-11-24.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger. "Apocalypse Now", Chicago Sun-Times, June 1, 1979. Retrieved on 2008-11-24.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger. "Great Movies: Apocalypse Now", Chicago Sun-Times, November 28, 1999. Retrieved on 2008-11-24.

- ↑ 'Napalm' speech tops movie poll, 2 January 2004, BBC News, accessed 18 February 2008

- ↑ Festival de Cannes: Apocalypse Now. festival-cannes.com. Retrieved on 2009-05-23.

Bibliography[]

- Cowie, Peter (1990) Coppola. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0306805987

- Cowie, Peter (2001) "The Apocalypse Now Book. New York: Da Capo Press.

External links[]

- Apocalypse Now (1979) at the Internet Movie Database

- Apocalypse Now at All Movie Guide

- Apocalypse Now (1979) at the TCM Movie Database

Apocalypse Now at Box Office Mojo

Apocalypse Now at Box Office Mojo- Template:Rottentomatoes

| Preceded by The Tree of Wooden Clogs |

Palme d'Or 1979 tied with The Tin Drum |

Succeeded by All That Jazz tied with Kagemusha |

Template:Link FA

Featured Video[]

External links[]